This summer I have decided to focus a little bit on Ancient Greece in my blog posts. First up, I thought I would give an introduction, just to set the scene. I’ve used a number of sources for this information; see the end of the post for a full resource list. If you already have a sound background on this time period, feel free to skip the following overview. If not, I suggest you do read as knowing the cultural and historical context in which a writer is writing will add to not only your understanding of the themes and style of writing, but also help with your critical analysis of the work.

There are many resources available today for the beginning student of Ancient Greece, some of them good, some of them not. I won’t try and recreate a whole unit of study on Ancient Greece here at this stage (though I may do in the future 😊) because for the self-educated student, working through a variety of sources is the best way to learn. What I will do is guide you through a brief introduction and then in the right direction for more information on Ancient Greece. This is also a great overview if you homeschool or would like to be able to help your children with their study on Ancient Greece.

Please note: The dates are all approximate as different historians put different times on each of these periods and many of them overlap.

If we were to imagine a brief, chronological timeline of periods in ancient Greek history it would look something like this :

* Minoan civilisation (3000-1450BC) flourished in the Middle Bronze Age on the island of Crete, in the eastern Mediterranean. Much of what we now know about this civilisation comes from the archaeologist and historian Sir Arthur Evans who named the civilisation after King Minos of Crete. Evans is also responsible for much of the rebuilding of the palaces at Knossos that tourists can still see today (if you plan to visit one day, take it with a grain of salt that most of what is there is a reconstruction of the ancient palaces - from the 1920s!) We also see the emergence of a pictograph based script (known as the Cretan hieroglyphs), as seen on the Phaestos Disc and also the still-undeciphered Linear A script. These are the first examples of written texts in Western history and are considered by many historians to be a pre-Hellenic script, un-related to Greek.

* Mycenaean civilisation (c1700-1100BC) overlapped the Minoan civilisation, but took in more of the surrounding areas of Crete, including the Peloponnese and the Aegean islands. It was influenced by the Minoan civilisation, with art, architecture, and religious traditions being assimilated into the Mycenaean culture. By the end of the 15th century BC, the Mycenaeans had replaced the Minoans as the dominant culture in the Aegean. Both the Minoan and the Mycenaean civilisations use of frescoes and pottery has helped modern historians piece together these puzzles of the past. Linear A script declined with the Minoan civilisation and was replaced by Linear B script, the oldest form of written Greek that we know of. The Amarna Letters (c1350BC) from Ancient Egypt (written in Akkadian not Linear A or B script) are a wonderful source to see how the eastern Mediterranean civilisations interacted with their Near Eastern counterparts. Trade was established with the Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians and other civilisations in the region, with the prominent trade being copper and tin, the main components of making bronze. It is wonderful to think of these ancient Greeks trading and interacting with the Egyptians and other ancient civilisations; they did not live in isolation as we can sometimes imagine from reading these histories independently. Archaeologists have also uncovered many artefacts made of gold, silver and ivory from Mycenaean towns, indicating a very wealthy society.

* When the Mycenaean civilisation collapsed circa 1200BC, it heralded the beginning of what’s known as the Greek Dark Age. This is a modern term, as none of the ancient authors refer to this time as such. This dark age coincided with the technological development of iron-working, thus moving from the Bronze Age and into what is generally known as the early Iron Age. Why the Mycenaean civilisation collapsed is a source of contention still open to debate by historians today. We do know that the Palace at Pylos burned due to fire as there are written texts (in Linear B script) outlining the event. There may also have been earthquakes around 1250BC. The Amarna Letters also mention a sea-faring people who brought destruction to the Hittites but there is no mention of them in Mycenae.

To me, this is one of the reasons why the past will never truly leave us: because there is still so much we don’t really know and when people don’t know, they continue to speculate, investigate and debate. This is what we should aim to do when studying any historical time period or text: investigate the facts (primary sources are preferable but secondary sources are also extremely valuable), learn them well, evaluate them and speculate new ideas or opinions about them (this process is quite obviously based on the standard classical education formula).

Pottery in the Dark Age took on a more geometric formula, as opposed to the established forms of Mycenaean and Minoan figurative art. Literacy appears to have disappeared across Greece. However, just as in the ‘Dark Ages’ after the fall of the Roman empire, we can see that many things were happening at this time in preparation for a new Golden Age (both Dark Ages were followed by a golden age – “The Golden Age of Athens” and the “European Renaissance”). The term ‘dark’ mostly refers to the fact that we lack information about this time. However, through the very use of the term, it is also expected that these were considered ‘dark’ times: a significant drop in population; a decline in material skills; a decline or loss of the fine arts (in this instance the loss of writing and literacy) and perhaps a general decline in living standards all characterised this period in the Greek world.

It is believed by some historians that the famous Trojan War took place before the Dark Ages began (at perhaps around 1300BC) but dating of this legendary event (if indeed it did occurred) is still debatable. Archaeological evidence from the last fifty to sixty years, suggests an invasion of migrating groups into the region which may also account for the decline. After the Trojan War, perhaps well after, we see migrating groups, the Dorians and the Ionians entering the region and establishing permanent settlements.

* Following on from this Dark Age, is a period now referred to as Archaic Greece (750-490BC). There have been significant discoveries in archaeology in the last fifty years to suggest that this time period was much richer in culture and innovation but also lay the foundation for the Classical period that was to follow, in areas of economics, politics, art and literature. Undoubtedly one of these examples would be Homer, who is acknowledged as being the creator of two of the greatest epic poems in Western Literature, The Iliad and The Odyssey. In his book, Archaic Greece, Snodgrass attempts to look at this time period in new light, bringing a fresh perspective to an otherwise forgotten time period in Greece's history. Main features of the Archaic period include a significant rise in population (after the apparent decline during the Dark Ages) and we see the rise of powerful city states such as Athens, Sparta, Corinth and Argos. The sharing of ideas and religious practices led to the building of beautiful temples for the gods, and a greater division of labour meant more complex social structures in these differing cities. At the beginning of the 5th century BC many of these Greek city-states joined together to fight against the powerful Persian army.

* It was during the 5th and 4th centuries BC that we see most of the accomplishments that came to be heralded as ‘the Golden Age of Athens’ or more famously (and inclusively), 'Classical Greece.' All of those glorious architectural feats in Athens and other areas of Greece, the figurative art so dominant in pottery, sculpture and paintings which went on to influence western art in so many different ways, the writings of some of the greatest western philosophers, democracy ...the list goes on and on! It was these accomplishments that have made Classical Greece a true paragon of western history. But don't be fooled that all of these accomplishments lead to peace or social cohesion. Much of the Greek world, which include the Peloponnese, southern Italy (Sicily), Asia Minor and areas in the Black Sea, still consisted of small, independent city states, often in conflict with each other.

One of the most vital examples of the glory of Athens during the 5th century BC is Pericles' Funeral Oration in 430. This speech is a shining example of the glories of that city state, spoken (and faithfully recorded by Thucydides) in a clear and succinct manner.

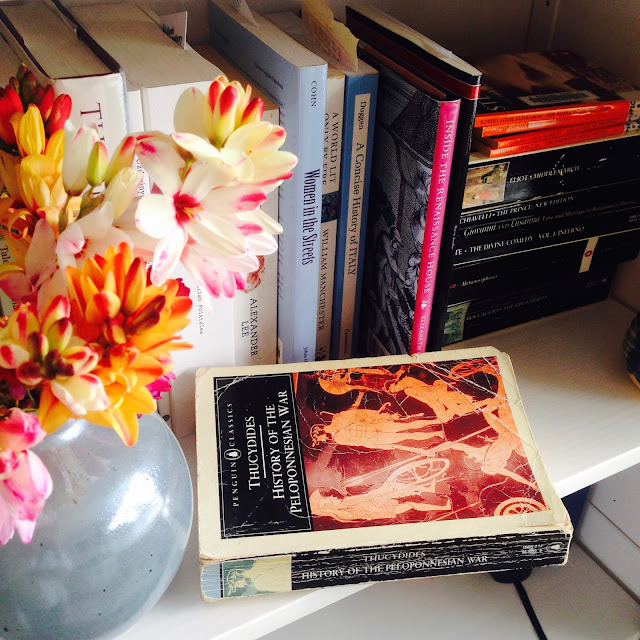

The Peloponnesian War was the most significant conflict during this period which led to the defeat of Athens at the hands of Sparta in 404BC. If you would like to read either Pericles' Funeral Oration (bk2.34) or Thucydides' entire history of the Peloponnesian War you can access it online here (simply follow the link that appears on the screen to go to Perseus).

Thebes and Sparta then continued to fight until, weakened by this constant warfare, fell to the new forces from the north, under the leadership of Alexander the Great. The Classical period ends with Alexander’s death in 323BC at the young age of 33.

The myths and religious stories that we are all so familiar with, were a dominant part of Greek society and culture at this time. A polytheistic tradition that permeated many parts of daily life, across all levels of society.

Historically we have been quick to praise the Athenians for their 'invention' of democracy, but we must keep in mind that only male citizens were entitled to vote. Women, children, foreigners and slaves were not. Nevertheless, it was a step in the right direction which lead western democracy down the road that it is still on today. It is easy to judge these ancient civilisations from our own cultural perspectives or paradigm, but I think we would do better to judge them in their own cultural context. Any sort of democratic action and say in the running of the government was a huge milestone for a region that had traditionally had only monarchies or oligarchies. Sparta, on the other hand, did not adopt a democratic form of government in the 5th century but remained an oligarchy. Of course, we don't have to agree with them now but nor should we ignore their role in history. History will always contain hard issues and the great thing is, they are still open to debate. What can we learn from them? What was done well that we can adapt to our own societies, our own lives? How have we, as humans, changed and grown? Where could we do better? This is the beauty of Classical Greece, as so much of what occurred during these two centuries is still fodder for our own moral and personal philosophies today. If we are educated in the history of the past we are able to pick and choose those aspects which will benefit the most of us today. We are not required to reinvent the wheel, but can simply modify it to suit our modern world.

* The Hellenistic Period (323 to 31BC) covers the time from the death of Alexander the Great to the rise of the Roman empire. During this time Greek world was characterised by large kingdoms or dynasties, as opposed to independent city states. The countries that Alexander had conquered took on many aspects of Greek culture during this time, including language, religion, athletics, theatres and so on. Even in Egypt a great library was built in Alexandria where many texts by the Greek philosophers and authors. Greece became a Roman province in 146BC however, the Greek influence is clearly seen in the culture and society of Ancient Rome.

In conclusion, I think that this quote from my grandfather's old book on Greece sums it up perfectly:

"One theme - the fragility of civilised life - dominates Greek history both classical and modern."

I think we could also add the fragility of civilisations dominates Greek history, as we have seen the rise and collapse of Greek civilisations in this brief introduction and there were many more to follow. I read recently that there are some people predicting the fall of civilised life as we now know it, and perhaps it is timely to look back on how other societies have dealt with this and what we can learn from them.

There are many who no longer see the study of Ancient Greece as important or significant, but clearly I do not agree!

In future posts I will discuss literature and cultural aspects of Ancient Greece and Rome. Hopefully now you have a fairly good understanding of the time periods I will use and the influence they have had on many societies and cultures that have followed.

Resource List:

- 'The Amarna Letters' by Elizabeth Knott, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/amlet/hd_amlet.htm 2016

- 'Archaic Greece: The Age of Experiement,' by Anthony M. Snodgrass, 1980

- 'The Dark Age of Greece: An Archaeological Survey of the Eleventh to the Eighth Centuries B.C.', by Anthony M. Snodgrass, 1971

- 'Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations,' by Mary Beard, 2013

- 'Ancient Rome,' by William E. Dunstan, 2011

- ‘Pocket Timeline of Ancient Greece,’ by Emma McAllister, 2012

- 'The Classical Greeks,' by Michael Grant,

- 'History of the Peloponnesian War,' by Thucydides, translated by Rex Warner, 1972

- 'Mycenaean Civilisation', by Mark Cartwright, https://www.ancient.eu/Mycenaean_Civilization/ 2019

- 'Minoan Civilisation,' by Mark Cartwright, https://www.ancient.eu/Minoan_Civilization/ 2018

- 'Greek Dark Age', by Cristian Violatti, https://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Dark_Age/ 2015

- 'Greece: Insight Guides,"edited by Karen Van Dyck, APA Publications 1989

Please note that previews of Snodgrass' books listed here are available on Google Books.

Comments

Post a Comment